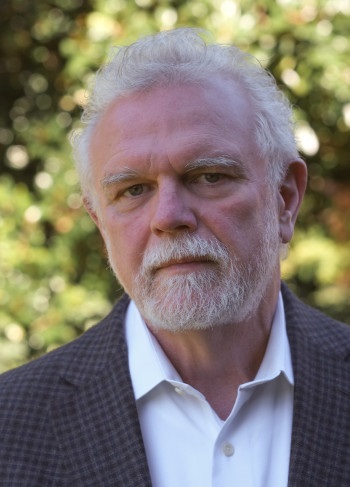

By Maria Browning

Major Jackson believes in the sacred practice of bringing together poets, poems and people. His most recent book, Razzle Dazzle: New and Selected Poems 2002–2020, was praised by Publishers Weekly for the poems’ “insight and warmth” and Jackson’s “capacious poetic world.” The New York Times described Razzle Dazzle as a “nutritionally dense smorgasbord.”

The culinary metaphor is apt; Jackson sees poetry as an art best appreciated in communion with others and approached through the senses as much as the intellect. He believes deeply in the power of poetry to break down barriers and foster understanding. His former podcast, The Slowdown, encourages listeners to put aside their hectic routines to listen to a poem and a brief reflection every weekday.

In his long career as a writer and teacher, Jackson has shared poems with a wide range of people—many of them new to poetry or uncertain about how best to approach it. Though he acknowledges that our interaction with poetry is “highly subjective, highly personal,” he has suggestions for how all of us can enrich our experience of the art.

FEEL POETRY IN YOUR BODY

Jackson stresses that the experience of poetry is fundamentally physical, whether we’re hearing a poem recited aloud or in the mind’s ear while we read. Poems, he says, “take us back to when we first learned language: how words felt in the mouth to speak.” He cites the late poet Donald Hall on our inborn response to sound. “Hall writes about how poetry even speaks to that innate sense of rhythm we have. When we’re in our baby carriages and our parents lean over and sing to us and we start kicking, our body starts moving—when you see little kids responding to that music, [poetry] is entering the body.”

“To experience a poem,” Jackson says, “is also to be sensitive to moments where the poet breathes: the line breaks, the punctuations, the pauses more obscurely known in English classes as caesura. Those moments of pause help us to modulate our own breathing. I always say to students, if you really want to experience a poem, memorize it and then walk while you’re reciting it because both that walking and that reciting become a way to have it enter into your body.”

DON’T FOCUS TOO MUCH ON ANALYSIS

Given poetry’s lyrical and oblique nature, it can be tempting to treat poems as puzzles to be solved, but Jackson feels this approach risks missing the point. “A poem is less about its appeal to our intellect, although that’s an important part of it,” he says. The key is “how it appeals to our heart and our sense of truth and emotion.” He quotes English poet John Keats, who spoke of “irritable reaching after fact and reason.” When we put aside “that desire to nail down the poem for what it wants to say to us,” Jackson says, we’re able to “open up pathways for the poem to do its work. If you do not demand of a poem any particular meaning, then what’s going to come through is the sounds, the nuances of speech and an attention to rhythm. I know a poem is good not by what it says, but by how it makes me feel and react.”

“Poetry requires three things: the poet, the poem, and the people. That is almost a holy trinity in itself.”

SHARE POEMS WITH OTHERS

“I’ve committed so much of my life to creating platforms or organizing readings,” Jackson says, “because I think it’s one of the most sacred means by which we come to learn who our neighbor is or how they experience the world. I know that when I hear a poem written by someone for whom I don’t share their phenotype or don’t belong to their demographic, I’m somehow made more aware of the width and expansiveness of humanity, a perspective I’m so grateful for.”

Jackson quotes the Black Arts Movement poet Etheridge Knight, who said, “Poetry requires three things: the poet, the poem, and the people.”

“That is almost a holy trinity in itself,” Jackson says. “The poem is mediating the relationship between the people and the poet. That is a connection that places a very important weight on the poem. It’s a formidable art for that reason.”

DEVELOP YOUR OWN COLLECTION OF DESERT ISLAND POEMS

Jackson advises having a few essential poems committed to memory. He notes that Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “Venus’s Flytraps” is one he returns to often, calling it one of his “desert island” poems. His other favorites include Robert Duncan’s “Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow,” Robert Frost’s “Birches” and “won’t you celebrate with me” by Lucille Clifton. “These poems live in me,” he says. “They’re sustaining. I think all of us need some sort of lifelines from poems to carry us into our day and into new realities. The need for consoling words, consoling metaphors, consoling rhythms is abiding for all of us.”

DON’T BE AFRAID TO LOVE THE POEMS YOU LOVE

Though many people are self-conscious about their taste in poetry, Jackson believes we should always embrace what moves us. “People feel pressure to perform a certain kind of intelligence around poetry or achieve a level of high literacy,” he says, but he notes that accessible forms like slam and Instagram poetry offer important sustenance. “For me, it’s all gateway drugs or gateway food that’s going to whet the appetite of someone who says ‘I needed to hear those words. I needed to read those words at this moment in my life.’ We do not need to feel any shame around it. It’s all meaningful at some level because it’s emerging from a human being.”